Review by Noah Vølund Fechter

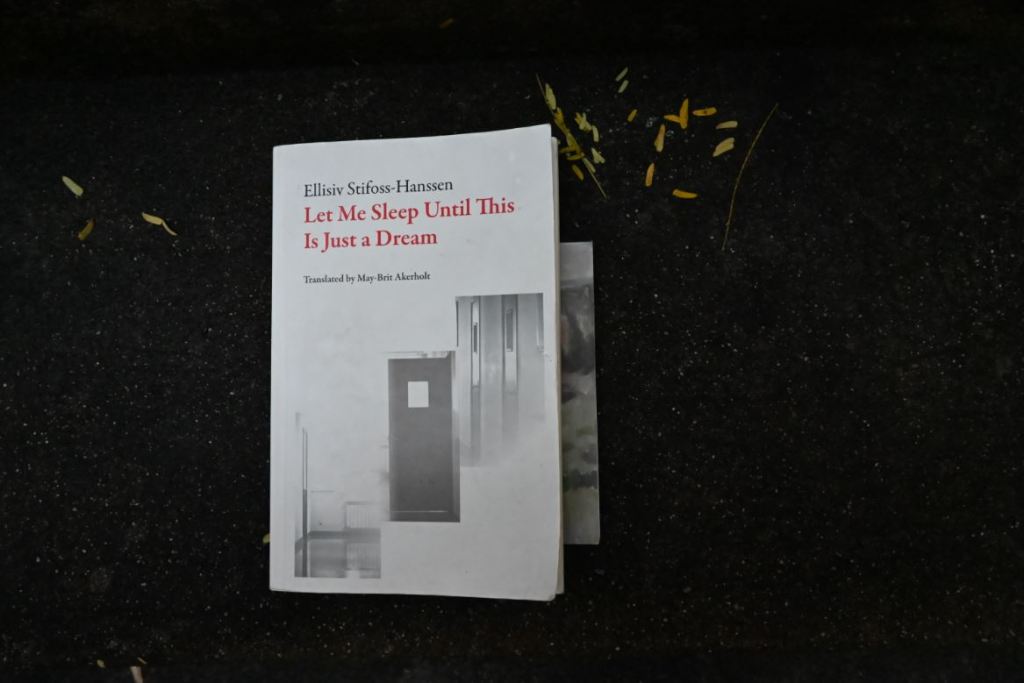

Let me Sleep Until This Is Just A Dream by Elisiv Stifoss-Hanssen, translated by May-Brit Akerholt.

Dalkey Archive Press.

87/100

Let Me Sleep Until This Is Just A Dream is an object of racking, teeth-grinding courage, beauty, humor, and vital force. (And that’s the Norwegian title too, pushed very neatly across the translation-divide.) It’s fragmented into sections often just one, two, three pages long; the paragraphs are a feat of fractal geometry, they’re themselves quite discretized.

Mia’s narrative skips across twee impressionist islands, by turns callous and cozy, from depersonalized hospital hallways to childhood home. She develops and recovers from cancer (a fact that, we’re permitted to know, has autofictional resonance), and often the paragraph ends as her treatment denatures her– too much pain, too tired, terrified to see her vomit everywhere, to see her legs growing small. The story winds up told in wounded time, it falters as Mia does. When a paragraph breaks, Stifoss-Hanssen pours a bit of time out of the hourglass, and when a section ends, the next starts up anywhere.

****

****

I don’t believe the reviews littering the book-sites when they say how sad the story is.

I remember being lighted by it. I wrote much of this review without looking back into the book, and I doubled-back to my writing to realize my sensations had been perfected by memory, by the massive gratitude which I’ve rendered onto Stifoss-Hanssen, in the three years since I read her.

****

It can’t be sad. For one thing the story is ‘comedy’ in the proper sense: it ends well. It’s also often comedy in the common sense. Mia’s all whimsy and humor, and in pain she turns more often to longing than to rage. So often the pressures, bloodflows, and vomiting simply tip the narrator over into longing, ‘what if Anne Marie were here,’– and when she is, ‘what if Kristin were here,’- she is constantly made uneasy by having someone or no-one near.

Mia’s pain often barely makes it to her speech, her narrative filters her experiences through a tiny sieve, to the point where each moment is performed staccato, the way that a child wants you to hear her thoughts. The sentence-forms in the book owe, to some extent, to syntactical differences in translation, but it is a prominent effect in any event. (“A sharp red box against a bright blue sky. That’s what the block was, the outside, the community. Enveloping me just as relentlessly as the weather. Refusing to be overlooking.”)

****

I read the slim book first on, I remember, a regional rail-line out to a little hospital building on Long Island, on a Saturday I volunteered to work (I’d already decided I don’t hate my bosses). It immediately inspired a season where I remember the evenings spent reading Monsterhuman, a massive also-white tome, massively unrelated, by Kjersti Annesdatter Skomsvold, another Norwegian woman-loving-woman named in another slight arc. I remember Let Me Sleep… had stuffed me with eager guilt, an absurd longing for the humor hiding in life’s pain and vainglory. I started to chase what else could make me feel that way. (I remember, especially, listening to Unithematic, in tramcars above an East River nocturne perforated by the seismograph-readout lights in the panorama of towering facades, nodding-in-and-out-of-sleep.)

****

****

I still wonder how much of the attraction I feel to Stifoss-Hanssen (and Skomsvold, alike,) comes from the crude hygge of the nanny-state, the rectilinear freedom of the characters’ lives (“‘We rich people have a good life,’ Dad says.”). On our side of the cultural gulf, it is striking that Mia even seeks to pursue writing (a fact, of course, with autofictional resonance), and it isn’t a plot detail that this is a precarious career. No, Let Me Sleep… couches itself entirely in the nearest thing to vulnerability which the Norwegian state will permit: convalescence, being uncertain if or when you’ll have your body again.

I want to say Let Me Sleep… is about sickness without waste, because in it I think only inevitabilities cause real and lasting grief. Mia’s sickness forces her thoughts into a place of continuous reckoning with the fragility of things, and the terror of her body’s resistance turning in on itself. (“Earlier, life was a circle. Now it’s a straight line. The shortest distance between two points. What if I survive, and have to go through this one more time, …”) Somehow I find this a fine way of thinking.

****

Freedom-from-insecurity affords Mia’s character some of the immediacy which we might otherwise feel in childhood exclusively. (I’ve heard it once as such: ‘only children have homes.’) It’s this freedom that allows Let Me Sleep… to function as a love story, about Kirstin and Anne Marie, each, weaving in-and-out of absentia.

The great heartbreak of the book – Mia’s longing for Kirstin, her once-fiance who she’d broken things off with, and Anne Marie’s feelings of betrayal when she finally learns of the former – is finally unsettled. One is never convinced that Mia has ‘chosen the right person,’ she’s never moved on. I imagine her absurd failure to navigate her own lovelife might read as antisocial or immature; to me, it’s the actual, typical, and familiar figure of desire in motion.

The book is also, against the figure of Kirstin-Anne-Marie-desire-longing-loneliness, a series of pieces informed by good and present parenting: Mia’s father is presented as limited, goodhearted, charming; her mother as limited, goodhearted, charming. We’re there for Mia’s father reckoning with his own feelings of helplessness, we’re there for their successes (“Nothing is worse than what you’re able to imagine, Mom has told me.”). I think I’ve only seen such a relationship, otherwise, in Bed by Tao Lin. In each case this life-in-rapt-belonging might represent the author’s memory polished into perfection. And it doesn’t read as eerie. I just believe it.

****

I gave a copy to Salomon, last year, when his father developed cancer; he would pick up, I thought, on the way the book follows intensity so closely that events become inevitable; the way that Stifoss-Hanssen truthfully renders moments when Mia is reinstantiated as a locus of feeling, sentiment, and receptivity; the way Mia’s desire is always-already remorse, too. And it ends and she’s freer and more vulnerable, in a white or beige room, clinging to someone strange.

I really think it’s not sad. I think it’s fine to give this book to your friend whose dad has cancer.

‘I liked it so much that it was non-linear,’ Salomon tells me. We’ve talked about the book some and it’s always thus: one of us makes a statement, and the other responds that that’s right. It really doesn’t matter that it’s about Norwegian lesbians, to us. I think Salomon’s dad, even if he’s fifty-something, must’ve felt like Mia in there; but neither of us ever say that, exactly. Today Salomon’s exhausted from weeknight karaoke and hiding in a marled sweatshirt. We walk the same block as always to where we’ll part as opposites; he’s going to fall asleep in his girlfriend’s bed, and I’m going to read the novella again.

It finally got cold in New York again.

****

What else can it mean that the linearity is disturbed, for Mia, than that the light of experience is worth holding as primary in our analysis, above and beyond our movements and moments, throughlines and thrownness? (“There used to be limits for which words it was necessary to express.”)

But I’m someone who sobbed at a certain point reading Chuangtzu, and Stifoss-Hanssen (and ultimately Skomsvold, too). I really don’t think it’s sad. In many ways I’m just glad that it’s like that.

****

Editor’s Note:

-The Roger Scruton quote “only children have homes” is here : “until right now I had no idea that’s specifically who said it; I know the quote because it’s said at some point in Patience (After Sebald), the 2011 Grant Gee docupoetry film with a Caretaker soundtrack” – Author.

–This is the closest the author has found to a statement of the book’s ‘autofictionality’. (“– Jeg hadde absolutt ikke lyst til å skrive om kreft, for det holder å ha hatt det selv. Men etter hvert ble sykdommen en del av historien jeg skrev, har Ellisiv Stifoss-Hanssen (f. 1980) fortalt i et intervju.”)

Unithematic is an album by Languis.

FFO: the early, somewhat-buddhist Tao Lin.

Buy Here.

Leave a comment