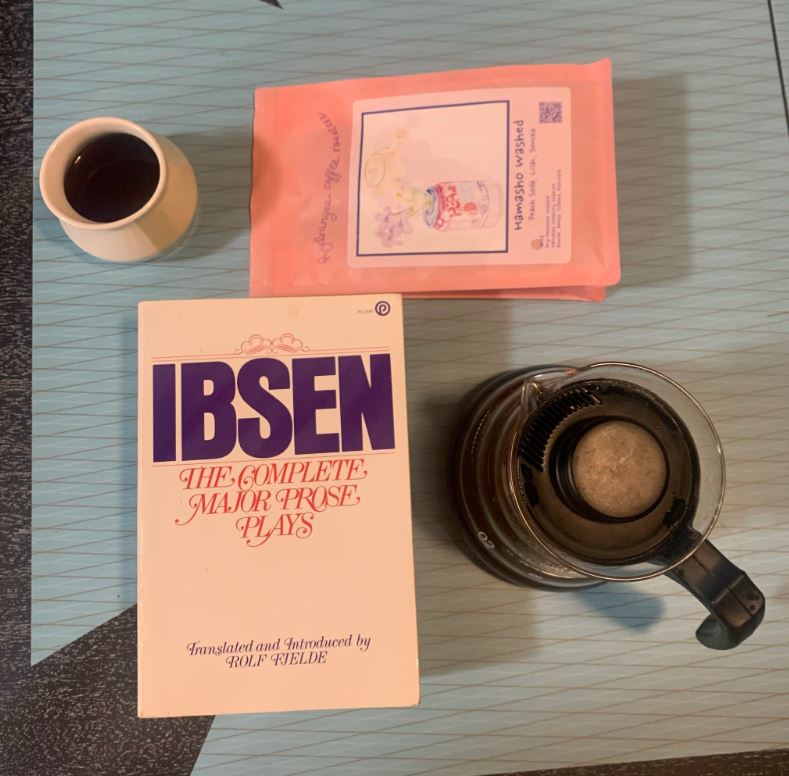

Review by Gregory Conway.

When We Dead Awaken by Henrik Ibsen.

Trans. by Rolf Fjelde.

Plume Books.

98/100

Over the course of an alarmingly over-caffeinated evening I decided to twitch through When We Dead Awaken (1899), by Henrik Ibsen. The play first entered my world after reading that James Joyce’s very first publication, at the age of 18, was a rave review of this Ibsen play. He considered it one of, if not, the best play by Ibsen.

The play was meant to be a turning point in the playwright’s career, an ending of a long series of prose plays, he planned to return to writing in verse such as his earlier works, ie. Brand (1865) and Peer Gynt (1867). Sadly, the playwright suffered a series of debilitation of strokes before returning to verse, leaving When We Dead Awaken as the master’s final play.

****

****

When We Dead Awaken opens on a sun-bright summer morning where the sculptor, Arnold Rubek, and his wife, Maja, are drinking champagne and reading the newspaper; the couple is silently overlooking a fjord outside a spa hotel.

Rubek is unsatisfied artistically and intellectually unstimulated, their flaccid vacationing lifestyle has turned to boredom, causing tension in his marriage to Maja. The plot unfolds when two characters enter the spa hotel; Ulfhejm, a rugged bear-hunter who takes Maja out hunting, and Irene, Rubek’s former muse who inspired him while he sculpted his masterpiece, called Resurrection. Irene and Rubek venture up the mountainside on a difficult mountainous hike, where they meet Maja and Ulfheim in the hunter’s ramshackle hut.

A storm approaches and Ulfheim and Maja descend the narrow path back down to the resort, grown quite dangerous in adverse conditions, with the promise of sending help for Irene and Rubek. When left alone, Irene and Rubek speak of their past and how they have felt dead since their earlier collaboration; they decide to traverse further up the mountain, above the storm clouds, to marry in the sunlight. Reinvigorated with life, as Maja also feels through her hunting hijinx with Ulfhejm. We can hear Maja sing as the play ends:

“I am free…No longer in prison, I’ll be! I’m as free as a bird, I am free!”

Singing as she descends, we hear her song as Irene and Rubek ascend the mountainside. Free at last. The adverse weather triggers an avalanche and Irene and Rubek are fatally carried to their death to the mellifluous sound of Maja’s song.

****

The play covers the complicated and powerful relationship between artist and muse, Rubek and Irene. Rubek’s great piece was created when Irene was his model. Irene resents that Rubek never made their love physical, though also telling him she was prepared to stab him if he ever tried. Rubek lets her know he always wanted to and had intense desire, but thought it would corrupt his great sculpture. As Megan Hanks writes for Commonwealth Theatre Group, in the late 1800s it was extremely common for models to double as sexual partners to their artists, modelling was perceived by the public as a sort of prostitution. Irene craved the physical affirmation of their love and now Irene constantly refers to herself as “dead”. She believes her soul was captured by the artwork and she has been “dead” ever since the end of their partnership, even referring to the sculpture as their child. The sculptor himself was also left “dead” in his own way, as Rubek never hit the heights of their work together and never felt the artistic connection with another, or himself, ever again. The work they created was a masterpiece, capturing their souls and leaving their lives empty, the walking dead. This can certainly be seen as a late-career Ibsen exploring his own mortality, how much of his life has he given to art? How could things have been different if an artist pursued happiness and relationships as opposed to artistic greatness?

The idea of Norwegian great work capturing a soul and leaving an artist feeling empty is more relevant than ever; what else is Karl Ove Knausgård’s My Struggle? (2009-11) The idea of someone being encapsulated in a work of art and left out exposed is just as relevant today in Norwegian literature, as we see in Helge Hjorth’s novel, Free Will (2017), showing the destruction great art can have on an entire family due to Vigdis Hjorth’s Will and Testament (2016). The growth of Norwegian autofiction and the real people being put into these works and exposed sees so much similarity in Ibsen. This play was incredibly ahead of its time and fits into the literary world of 2025. Would a couple drinking champagne, who have fallen out of love, setting out on two different journeys with an animalistic young man, an artistic muse from the past, and a suggestion that all three, Rubek, Maja and Irene all live together as a couple feel out of place in the new Edy Poppy collection? I think not.

****

In reading Ellen Rees’s book Cabins In Norwegian Literature (2014), I read about the idea that Ulfhejm, the bear-hunter, was partially a parody of Fridtjof Nansen, a zoologist and explorer who was a contemporary to Ibsen. Sigurd Ibsen, Henrik Ibsen’s son, was passed over for a professorship in Sociology days before Nansen was granted a professorship, which according to another scholar, Tor Bomann-Larsen, proposes this was part of the motivation to start writing When We Dead Awaken.

The inspirations for the characters in this novel are far-reaching. The relationship between Rubek and Irene is similar to the relationship between Laura Kieler and Henrik Ibsen himself; a young Laura wrote to Ibsen when she was 19 and he helped nurture her literary ambitions as a mentor. Laura’s marriage to her husband was the basis for Ibsen’s great play A Doll’s House, Laura never forgave Ibsen for exposing her and using her life as fodder for the play.

In another way, Rubek and Irene are also Auguste Rodin and his student, lover, and co-worker Camille Claudel; this is generally the most written about relationship. Claudel, a muse who changed Rodin and pushed him to greatness, was “dead” in her own way after the end of their collaboration, languishing in mental hospitals and asylums for the last 30 years of her life. Irene, in the play, is also worried that she will be taken to an asylum throughout When We Dead Awaken.

****

Another gem in Ellen Rees’s book is a reference to Armand V (2006), a novel by Dag Solstad. Solstad famously couldn’t write more than 10 pages without reference to Ibsen, his books a life-long love letter to the dramatist. Armand V uses the imagery of When We Dead Awaken to show realization. In the play, Rubek makes references to his sculptures featuring hidden images. They appear as simple busts, but to him, hidden deeply in the pieces since his separation from Irene are distorted pampered pig snouts, low-browed dog skulls or the heavy, brutal semblance of a bull. Armand, near the end of the novel, after realizing the error in not voicing his opinions against Norwegian intervention in the middle east, sees the American ambassador in Norway, through his bust, and sees his Pig’s Head.

****

The play also switched from an original ending where Ulfhejm toasts all four characters with champagne, as they have all found their own sense of freedom. Maja and Ulfhejm head back to the spa hotel as Irene and Rubek ascend the mountain above the clouds, a Nun looks up to the mountainside and remarks on the sunlight and shine above the storm. In the original ending there was no avalanche. In the original ending we do not see Irene and Rubek tumble to their deaths. However, yes, Irene and Rubek tumble to their deaths and Ibsen never returned to writing verse.

“I am free…No longer in prison, I’ll be! I’m as free as a bird, I am free!”

Pax vobiscum.

****

FFO: Wilderness, Plays, This Blog.

Buy Here (A Different Translation)

Leave a comment