by Ursula Carroll

I could tell from her books, Anatomy. Monotony. and Coming. Apart., Norwegian author Edy Poppy is the kind of woman I want to be friends with. Her books are the work of a woman who is self-assured, cool, and has a clear viewpoint on how we interact with each other. Women like that are almost always witty, insightful, and easy to talk to. My suspicion was right. I replied to a confirmation e-mail the day of our meeting at a preposterously early hour, and she sent back a prompt “Are you awake? We could talk VERY soon, in like ten minutes?”.

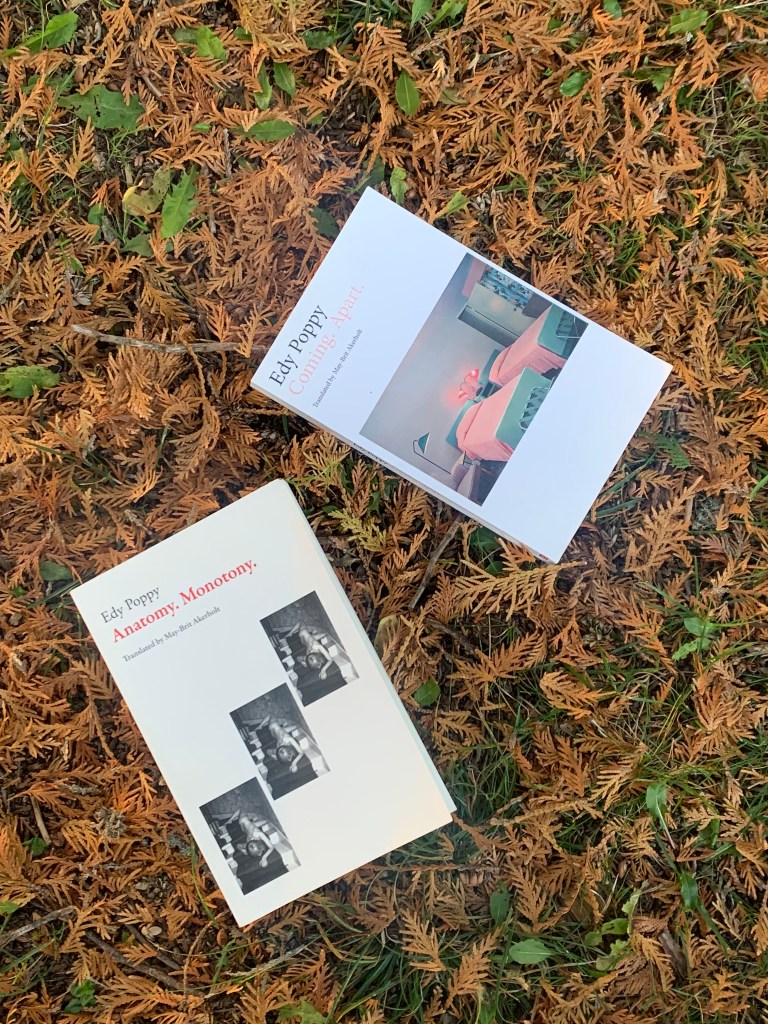

Poppy’s debut autofiction novel Anatomy. Monotony. (published in English in 2018) is a very honest, unafraid look at her open marriage. It is expertly paced, drawing the reader into a whirlwind period in Vår’s relationship with her French husband Lou and her lovers, blisters and all. Poppy writes about all of the pleasure, all of the joy we can experience opening ourselves up to other people, and the ways in which we allow ourselves to be hurt for the sake of this ecstasy, for gratification and love. Poppy’s second book Coming. Apart. (published in English this October) is the opposite. It is an intense and compelling collection of shorts. Shorts about the ways in which we first pull together, the excitement and rush of getting together. Then pull away, pull apart, hurt each other – intentionally or not – separation, pain, breakdowns. A marked shift in subject matter but the writer’s voice remained consistent: confident, descriptive, sensory.

I was excited to talk to Poppy. Coming. Apart. is the kind of book you open and don’t put down until it is finished, and I had a lot I wanted to discuss. She and I met on Zoom, at 1:30 pm Oslo time, or 6:30 am St. Louis time. Poppy had just returned home from a book tour in the states, having been in New York, Dallas and San Francisco right before we met up. She said that she had been reading Intermezzo by Sally Rooney and Oh William! by Elizabeth Strout while she was traveling. Rooney had been a surprise, she explained, because she’d already seen two TV series based on her stories and felt like she didn’t need to read the books, but she was mistaken. Rooney’s literary style, the depth of her character’s inner life, the intriguing plots and how she describes sexuality fascinated Poppy.

Human sexuality is the overarching theme in Edy Poppy’s work. In a way, that is the lens with which she has chosen (or perhaps, has chosen her) to explore complex themes. She said-

“We are defined by if we are having sex, if we are not having it, if we are happy about that, if it is good or bad, pleasurable or traumatic. Sexuality can be a way of relating to people that is without class, you might sleep with someone you hate, you could sleep with a stranger, an enemy… It can be a short cut to intimacy, or to distance. For good or bad, sexuality is a rebel, an animalistic side in us humans that society has not yet managed to tame. Without sexuality, I think the world would be much more predictable and conformist” Both Anatomy. Monotony. and Coming. Apart. are books about relationships, about love and pain, using sex as a mirror to explore the subtleties of how we exist. Make no mistake; her books are not pornographic, they are not erotica, they are literature. “In Germany, Anatomy. Monotony. was labeled an Erotischer Roman. “I feel bad for whoever was reading it with their dick in their hand,” Poppy laughed. “When you label a novel erotic, it frames your reading. The sex in my books is not there to please anyone, it’s there to say something about the human condition.”

Poppy explained that when she moved to France at 17,

“everybody wanted to talk about sex, and often in an intellectual way, for instance with references to French philosophers, like Georges Bataille or Roland Barthes. That was inspiring. As well as Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre’s open relationship, or French films, like François Truffaut’s Jules and Jim exploring a ménage á trois, etc. Having a new language to talk about sexuality, as well as a new way of looking at it through the French culture, opened up my vocabulary, and thus my feelings about the subject, in ways that Norwegian language and culture had not been able to do.

Adding: “Norwegian only has very vulgar, clinical or uptight terms for pussy; fitta, vulva or venusberg; and French has nuance.” In cold Norway, people are more buttoned up, it is a more private culture. Not really conservative, per se, but more reserved. With this new vocabulary, Poppy found new ways of relating to others and to herself. Back in Norway, there is a tendency to avoid sticking out, to avoid tall poppy syndrome, if you will allow me this pun. Upon moving to France, Poppy changed her name from her rather old fashioned Ragnhild Moe to Edy Poppy, adopting an artist’s identity. She thought people back in Norway might judge her for using an artist name, but to her surprise, it seemed to inspire some to change their names too. Despite writing extensively about female sexuality; an eternally taboo subject; Poppy was not particularly concerned about her reception in her small hometown of Bø in Telemark upon her literary debut.

“I have a lot of fear whilst writing, I go into domains that might be painful for me to explore etc. But through the process of making those difficult, or shameful experiences into literature, the fear disappears. I was a little concerned about my parents, though. My father was a school principal at that time, and my mother was a teacher and politician. Would they be ashamed of their daughter, I asked myself? Thankfully they were just proud. And relieved that plan A, meaning me becoming a writer, worked out. I had no plan B, which scared my parents immensely. If you have a plan B, you will use it, is my theory.”

Anatomy. Monotony. and Coming. Apart. are books about discomfort, pain we inflict upon each other. Anatomy. Monotony. welcomes the pain for pleasure’s sake. Characters willingly play games with each other they know will hurt, in the name of love and delight. Coming. Apart., it is amped up. There is deception, contempt, desire gone sour, revenge, violence, sometimes to rather extreme levels. I asked Poppy if she thinks it is possible to exist with each other without hurt, as it is such a fundamental part of the human experience. “Some people read Anatomy. Monotony. as an inspiring way to have a new kind of relationship, no matter the cost, thinking, ‘that sounds fun!’ And others see it as too painful (but still interesting to read about) and could not understand why you would do that.” While Anatomy. Monotony. was written when Poppy had an open marriage with her French husband, Coming. Apart. was written after Poppy’s divorce, that he did not want. This is no secret, the book opens with a memorial to her marriage: Cyril and Ragnhild 7 November 1992-13 June 2008. “I think male (love) pain, the man left behind, being betrayed etc., is underrepresented in literature, and I wanted to explore that”. In Dungeness, for example, there is a man who is told from the beginning by the woman he loves that she “moves from one relationship to another and stays with whoever desires her the most.” What results is a gripping short about a man who loses control of himself, his sexuality. He becomes pathetic and desperate in this grey seaside town, Dungeness, for the sake of this woman he knows will leave him. It is a highlight of the book.

Poppy went on to tell me that Dungeness was originally written in English for an English magazine in the 1990s. While living in London, working on Anatomy, Monotony., she’d been writing shorts in English and sending them to English and American magazines like Tank and Purple. After her debut was awarded the prize for the best love story by Gyldendal in 2005, Norwegian magazines came knocking for more work. Poppy said she is a slow writer. She started translating her English-language shorts into Norwegian and found them opening up again. Dungeness was just five pages when I first published it, but after rewriting in Norwegian more than ten years later it became longer and longer, new details being added. Like the strange mother who comes to visit every time her daughter has a new man. In this case her daughter leaves the house when she sees her mothers’ yellow Beetle through the window. Leaving her new man to take care of her mother alone, though he has never met her.I asked Poppy if it was the language itself adding room to the stories, but no she said.

“When I send a story off it is locked, but when I started to translate it, it was like it unlocked. It came to life again, hungry for more words, more scenes, secrets, more things to happen. Spending seven years in London and traveling to the US often, the English language is a real big part of me, of who I am.” She smiled, animated discussing this period. “ So the English versions of my books are sort of the real thing too. The reader is not missing anything by reading the translation, which I look at very closely. On top of that I have a wonderful relationship and collaboration with my translator, May-Brit Akerholt, who also translates Norwegian Nobel-prize winner Jon Fosse.”

Portions of Coming. Apart. are so intense, unsettling, disturbing in ways that surprised me. Boils is one such an entry, a domestic body horror short about resentment and contempt. It felt so remarkably different from the cerebral scenes of bodily delight in Anatomy. Monotony.; it really stood out for me. “It’s secretly about a much younger boyfriend I had after my divorce and we were actually giving each other boils at the end of the relationship,” Poppy said of her inspiration.

“It was real passion at first, but the boils understood, before we admitted it to ourselves, that something was not right seven years later. Our once so vivid love affair had suddenly grown old, lifeless. I wanted to explore that metaphorically by turning us into an old couple and giving “him” the voice, letting “him” look at “me” through his now unlovable gaze. Surprisingly, humiliating “myself” in my writing can be quite fun, and healing.”

There is real emotional truth through all of the shorts in this collection, though less direct than her previous novel. None of the ironic detachment, no keeping vulnerability at arm’s length. Poppy has figured out how to walk the line between too honest and too removed. In Anatomy. Monotony. the main character, Vår, writes a novel within the novel, and that book is the story of Poppy in her real life using her and her husband’s birth names Ragnhild and Cyril. For that, Poppy returned to her diary. “To my surprise I found that the entries in my diary were not true emotionally, just factually. To get closer to the real truth, the fictional truth, if you like, I needed to invent, to extend my diary reality into the unknown.” She admires the literary honesty in the work of French feminist autofiction writers like Duras, Ernaux, Christine Angot, and most recently Constance Debré. “I think there is bravery in being cruelly honest. Irony is hiding something.” Poppy has invented a term for the moments she encounters and feels compelled to document. Writeogenic–

“it is like photogenic, but for writing. Some things aren’t meant to be written, they sound good in my head, very dramatic and crazy, fun, but fall flat on the page. Other things hide in my fingertips and I would never have known of their existence if it weren’t for the act of writing. Only when my thoughts hit the page can I see if they are writeogenic or not”.

This concept is elucidated during the moments in her writing that feel like true snapshots of time, snapshots that perhaps the reader has even experienced. Maybe you’ve discreetly slipped an ashtray, or a glass into your bag from a bar or maybe you have moved your chair ever so slightly in the windowlight of a cafe to stay in the shadows a bit longer. Poppy claimed that the more personal her writing becomes, the more she is writing about you, the reader.

Parts of Coming. Apart. feel like closure, like an end to the Ragnhild and Cyril, Vår and Lou, that we knew in Anatomy. Monotony. The book begins with The Last Short Story, opening with Vår, the main character, having a sort of creative breakdown, wondering if she should scrap the short story collection and start writing something new, a novel. “I sent The Last Short Story to my editor in an e-mail and she thought it was real. She wrote back immediately, trying to calm me down”, Poppy told me. Rain Border has Ragnhild and Cyril celebrating their wedding anniversary in a very final way. “Anatomy. Monotony. is me in my 20s, Coming. Apart. is me in my 30s, my next book Iggy (which I hope will be translated into English soon) talks about me from my teens all through my 40’s (from 1995-2017), introducing new exciting characters, like my German performance-artist boyfriend, Julian Blaue, whom I live with in Oslo these days together with our three kids” Poppy said. As for when the next book Iggy is coming, there is nothing set in stone just yet, but hopefully we’ll be graced with something in the near future. I’ll be waiting.

Poppy was so kind and generous with her time, and as we parted ways, she said that I’d have to make a trip to meet in person if any Midwest book tour dates arise. I just got word that there are a few fall Midwest speaking engagements in the works, so it looks like I have some traveling to do.

tyvmnpgmw

Leave a comment