By Gregory Conway.

A.V. Marraccini (she/her) is critic, art historian and essayist based in New York. I came across their work through their wonderful book We The Parasites (2023), out in Canada on Boiler House Press (Sublunary Editions). Their next book, THESE NEW FRAGILITIES, will be out with 7 Stories Press in 2028.

Erkka Filander (he/him) is a part of Poesia, an independent and co-operative publisher in Finland where he is the head editor of the Poesiavihkot chapbook series. A winner of the Helsingin Sanomat Literary Prize for their own poetry. In June, 2025, Erkka published Siemenholvi [Seed Vault], an ambitious and experimental book of poetry, which has won the Varsinais-Suomi Art Prize & was nominated for the Runeberg Prize shortly before this interview.

****

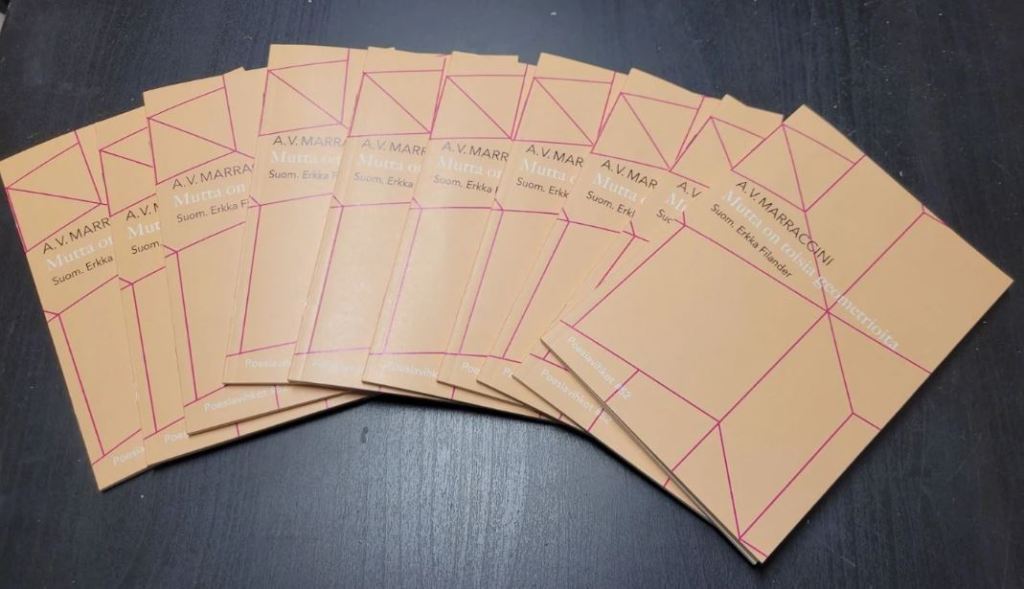

A.V. Marraccini’s 2024 essay, But There Are Other Geometries: On cubes, love, and fate, has been translated into Finnish by Erkka Filander for Poesia and shipping out over this holiday season.

I popped into a chat with A.V. & Erkka about their collaboration, literature in Finland, translation, Poesia, Glenn Gould, pronouns in Finnish and Paimio lounge chairs.

****

****

LP: Good morning from Peterborough! Thank you for joining the Lønningspils Google Chat. I once again stayed up way too late reading Par Lagerkvist short stories, but am otherwise golden, how is the day going in New York & Turku?

AV: COLD here at least which is a funny thing to complain about vs Finland.

EF: It’s soon 7PM here, I’m drinking coffee and eating some fresh baguette, so I’m all set for this conversation. Here it’s mainly wet at the moment. Wet and very, very dark.

****

LP: The dangerous 7pm caffeine kick… Its also frigid up here. I guess to start it off, we are here to talk about a chap book publication in Finnish for Poesia, could I ask how this collaboration came about? As a big fan of Nordic Literature and We The Parasites, it’s really an exciting project to me.

EF: I first became aware of We the Parasites, A.V.’s book, and only then I found her online. It must have been her writing on Cy Twombly which caught my attention, as I was basically reading everything ever posted online about his works. Then I read her essay “But There Are Other Geometries” almost immediately after publication and the text stayed in my head for a long time. I was very moved and influenced by how it carried its references and how the syntax flowed and jarred and had a very particular friction to it. Some time later I contacted A.V. via DM and suggested this translation. As the editor of Poesiavihkot (our chapbook publication series) I try to be on the lookout for texts that would suit our catalogue, texts that would work in some sort of an intuitive constellation together. A.V.’s essay spoke to that as well, to our larger catalogue and how I saw it, the series, could partake in something new through her work.

AV: I’d like to add that in speaking a lot about other things, we came to realize how much we have in common about what we want for literature in general long term– and how literature in translation can encourage hybridity and difficulty. I’d like this collaboration to go both ways, and to see Poesia’s authors get the attention, translation, and distribution they deserve in English. For me part of this is also work as a critic who loves work outside the novel that challenges what we think writing can do.

LP: A.V. to speak on working “outside the novel”, as I’ve been describing your piece to some friends over the past couple days I have really been drawn to that “challenges what we think writing can do” part. I’ve used the terms “Essay” “Essayistic Poem” – “Poetic Criticism” even “Auto(non)Fiction” & “Secret Third Thing” to describe the piece, do you have a term you blanket your style with? & how did you come into it? It feels truly unique.

AV: It’s strange, because English is my native language, but I’ve never truly felt at home in the publication world of Anglophone authors. Even my current publisher in America, Seven Stories, is really known for their translated titles. Broadly, I would say I do “lyrical non fiction” or “lyrical criticism” because there’s an associative aspect to the lyric form I want to gesture to. Recently I’ve been working a lot in linked epigrams, although my next book is an extended essay in sections. In any event, I’ve noticed my stylistically more avant-garde approach to objecthood, historical context, ekphrasis as practice, and textual citation across language is much more common in say, Germany, France, and the Nordics than in the market for native Anglophone nonfiction. The National Library of Sweden ordered a copy of We The Parasites far before many American universities did! Part of the reason I have the freedom to write like this is my readers are often themselves non-Anglophone or have expectations garnered more from literature in translation. This cuts both ways though– it’s hard to get publishers and magazines to take those kind of stylistic risks in English, though that’s changing as my profile gets a little more known. Still, outside my books, I tend to write in places like the Berlin Review (which ran one of my recent pieces in German translation as well) or the Cleveland Review of Books, rather than the typical “prestige” English magazines. I think I have more in common with Poesia’s catalogue than the catalogues of most American publishers!

LP: On fitting in with Poesia, when I found out your work was being translated to Finnish, it made sense to me as I’ve only connected your style to one other writer, Kari Hukkilla, a Finnish writer working in a kind of essayistic innovative novel style. There really is a more open-minded nature to exploring the boundaries of a “book” outside of North America.

****

LP: The Runeberg Prize was won last year by Pirkko Saisio. Alongside Kari Hukkila and Eeva-Liisa Manner, those are really the only books I see my friends who love literary in translation pick up for Finnish Lit. I feel there is a whole world that is unexplored in translation. Is there a reason why Finland isn’t seeing the translation boom that we are seeing in Norway / Denmark / Sweden ?

AV: Practically speaking, in the American market, translation booms are often subsidized by other governments, since independent presses have no money to speak of and we have lost so many public grants for the humanities. Korean literature benefitted from this recently.

EF: The obvious answer is the Finnish language. There simply aren’t enough translators, publishers, agents, readers, critics etc outside of Finland to raise the profile of Finnish literature, to point others towards Finnish books. And there’s actually a second obvious answer, which is money. The other Nordic countries have had a lot more robust international strategies for their literature and its export, and they have a very different situation re: financing cultural projects. These are very boring answers, but I think these, sadly, cover much of the blame. The very last thing the Finnish government will do is give more money to literature.

AV: Also, I think there’s this cultural problem in that in the design and architecture space, postwar Finland is seen as a very robust exporter (think Aalto buildings and chairs, Marimekko textiles) but in literature for some reasons US-Americans see Moomins and Kalevala. Which is so unfair! Well the American government ALSO doesn’t give money to literature. So I’m begging your university or foundation, fund Finnish literature in translation!

LP: Outside of literature I mostly think of the hockey player Teemu Selänne & Samuli Pääkkönen’s coffee roaster in Turku called Frukt (world class!)… I really need more literature in translation to open my eyes to the country…

EF: I used to live in the opposite building from Frukt. I almost feel a sort of vertigo to have it mentioned in this context.

****

LP: Circling back to “not enough translators”, you are working with Poesia & working on your own poetry: is translating something you are looking to dedicate more time to? Where does it fit into your craft & life?

EF: A.V.’s essay was my first published translation, but I’ve done translations as long as I’ve written. It has been very often my way into a poem – when I was a teenager I did translations of Keats’ poems because I wanted to be in them, not just read them, but somehow go into them, press my face into them like you would into a lake or a pond. This practice has continued ever since. And my latest book includes a lot of small, miniature translations, fragments of translations, small shards of translations I’ve done solely for that book (without mentioning they are translations and without providing sources). Yet I think translation will have more focus in my work going forward. Not merely as an exercise or way of analysing things, but as a craft of its own. I’d love to have time and funding to translate A.V.’s We the Parasites. And a lifelong dream of mine has been, and still is, to make a new translation of Dante’s Commedia, but that’s another, more obsessive and hubristic story.

AV: I also, coincidentally, did imitations of Keats in English as a teenager. Chapman’s Homer is very crucial for both of us I think, as a feeling.

****

LP: Speaking on the Finnish language, which I am really not familiar with myself. I wanted to touch on the third-person singular and how there is only one pronoun, giving potential for androgynous & non-gendered poetry, which is lost in translation and even translated to “he” in English. If I am understanding that correctly?

AV: This actually came up with the essay because it’s about the end of a queer love affair! I would have loved to have such a pronoun to use in English…

EF: Yes. So the only third-person singular in Finnish is “hän”, which is used regardless of gender. My first book leaned heavily on this androgynous use of hän, I wanted to create an atmosphere of lust and bodily intensity without really specifying the genders in those more intimate and intensive moments. When the book was translated to Polish we had to choose a gender for the hän used in the poem (and we decided on he/him, even if it felt wrong). There have been attempts to coin new pronouns for genders, for example “hen” for the feminine third-person singular, most famously used by the poet Leevi Lehto in his seminal translation of Joyce’s Ulysses. But these attempts remain flashes and haven’t gained traction into general use.

And of course this was a problem we had to confront almost immediately with A.V.’s essay. We decided to use cursived hän/hänen for she/her pronouns to signal when it was about this particular person, when the pronoun felt extremely personal. This had to be done somehow in Finnish and that felt the best, if not the most subtle, way. “Hän” is an incredible gift in this language. And you can imagine the possibilities it gives to poetry, to queer writing, to ambiguity…

****

LP: I was chatting about this with my friend Eliza last night at my book club as we were chatting about a chapter on layers of meaning/messages. A built in pronoun like that would really eliminate a lot of the implied meaning people read into “they”.

We are reading Douglas R. Hofstadter’s Godel, Escher, Bach, which feels an appropriate side study to your piece which leans on Glenn Gould & Godel, though as a Canadian I couldn’t bring myself to listen to the other pianist doing the Goldberg Variations you mention in your essay, sorry Vikingur Olafsson.

Did you end up seeing the performance at Carnegie Hall you mention having tickets to at the end of your piece?

AV: I did and I cried! Despite loving Glenn Gould and Said’s essay on him in his book on late style very much. Actually, the virtuoso tenor and innate difficulty of late style as Said presents it are things I think Erkka and I both prioritize in literary work. And something I think readers would see more of if we had a more diverse corpus of work in translation.

LP: I’ve been imagining the kind of life I would have if I built a 14 inch chair and typed Glenn Gould style…

I wanted to touch on accessibility of criticism. I love We The Parasites and your piece being translated because it offers criticism outside of academia. I can buy We The Parasites from Boiler House Press for like $20… where your writing on Twombly, Updike, Gould ect, could easily make sense and feel at home in a University Press book that would run me $250.

AV: I thought about going to a university press at one point and had the most unprofessional, negative publishing interaction of my whole life, which ended up being good in that I really doubled down and committed to my literary style. BUT literary presses are often hesitant to print referential works because they consider them “scholarly”. I am lucky to have Seven Stories in an era when people don’t know who say, Diderot is, and resent being asked to look it up. You have a phone with easy access to wikipedia on it! Reading is not meant to be easy and effortless all the time! (Montaigne complains about this, it’s not a new complaint for essayists) BTW I say Seven Stories here since I’m referring to my next book, These New Fragilities, that I’m going to Tokyo in about two weeks to finish. Plus I’ll note in today’s political climate, university presses won’t always stick up for you. My next book opens with classical Japanese waka, Sarah Kane plays, and French rococo painting as counterpoint to images of atrocity in Gaza. Which I called a genocide in a sample chapter in November 2024, so, in the end, since UPs won’t endorse PACBI and are all scared of blowback, leftist authors end up at indies like Verso, Feminist Press, Polity, Seven Stories etc..

****

LP: You seem to soak in your entire life into your words… Twombly, break ups, Updike, Greek classics, horror movies, ect. Has anything inspired by Finnish Lit touched down in the mustard yellow Leuchtturm notebook?

AV: hahahah I actually am still on the maroon-oxblood one but YES, and it turns out Erkka and I share many obsessions, like the Svalbard Seed Vault for which his most recent book is partly named.

I want to go to Helsinki this summer so hopefully my third book will include a significant “Finnish section”. I also would love to work with Erkka and Poesia on a joint project sometime in the future, ideally in both languages at once. There is a time lag with books, so the second book is Gaza-French Rocaille-Tokyo undergirded with my own move here. But the next one… hellooooo Finland! I look forward to that coffee shop in Turku.

I am very excited about finally seeing the sinks at Paimio. I teach students the sinks every term I talk about humane thinking and design/architecture. Postwar Japanese architecture is in my second book, These New Fragilities, which does have a strong relationship to postwar Finnish architecture and global modernism.

(the sinks were angled to be silent so doctors could wash their hands consistently without waking up the patient every time; also the famous deck chairs are angled to dispel sputum in the lungs from tuberculosis)

****

LP: I wanted to mention something special about Poesia. There is a publisher here in Canada, Coach House, which also has a Heidelberg Press on their main floor. Poesia also has a Heidelberg (printing/letter) Press in house, I love to see publishers actually engage with physical books. It’s special to see something actually produced in downtown Toronto. My dad ran a Heidelberg Press for a living, so I have memories of being around them as a kid and love to see them used in creative endeavours.

EF: Wonderful to hear someone else is out of their minds as well. Our Heidelberg is actually in the cellar of the mother of our publishing director! It has lately been in little use, but we used to do a lot of our covers with it, two of my first books included. Also Raisa Marjamäki and Olli-Pekka Tennilä have done whole books with the letter press. My memories of the process is being huddled with other poets in a small cellar room filled with mechanical devices and paint pots, everyone smoking cigarettes and dancing to the worst music imaginable. That for three, four days straight. It’s wonderful.

The original idea was of course to seize the means of production.

AV: The whole enterprise of translation and what we do as writers, for both of us, is pretty intrinsically anti-capitalist. I mean does anyone make the big bucks on difficult hybrid literatures? Hell no!

****

LP: Has the Finnish A.V. Chapbook been released already, or soon?

EF: The chapbooks will arrive tomorrow to our offices! And then we’ll have our winter party for our writers and friends and it’ll be available then. It will also be sent to the subscribers of our publication series. We send five chapbooks a year to them, all of them surprises and in no way announced before they arrive. I find it exhilarating to use surprise as one method of publishing.

AV: The cover is REALLY cool btw. By the poet Petra Vallila!

Look, Poesia has built this whole infrastructure in Finland for literatures that challenge what a book can be. Which, even though I write in another language, is fundamentally always my goal as a writer. As a critic, now is my chance to yell a lot about how much I want to see their work in English because that is also what I think is good for us intellectually to have access to.

Susan Sontag rather famously did a lot of this for Eastern European cinema and and literature. I don’t have that kind of fame. But I’m loud and on the internet a lot. This is a thing criticism can do.

And if my critical voice is worth anything aside from my own written worth, I would love a publisher reading this– and many independent presses, you know me, email me, DM me whatever!– to contact Poesia and bring their authors to English. Because English only readers deserve access to that kind of thought and it deserves a wider audience here.

****

LP: I think to end on, are there any writers in Finland that the English market should be aware of that are either heavily under-read, or untranslated? (apologies for putting you in a tough spot to narrow down!) & what books do you two have open these days and are enjoying?

EF: I will preface my answer with a note: I won’t be answering this as in my capacity as a representative of Poesia, but as a reader and a writer. This is a very personal selection, with all the possible biases that you can imagine.

But the names that immediately come to mind are the poets Raisa Marjamäki, Kristian Blomberg and Olli-Pekka Tennilä. Their work, I think, has brought something new to Finnish poetry, a Finnish fragmentary poetics, that is, in my opinion, quite unique. Their work is very different from each other, but their work has influenced my own the most, and not just my writing but my ethics as well. I think their work would astonish English readers in the way their poetry thinks in the moment, but also in how the books create this overall tension and structure in a manner which is not very common in the English poetry I’m familiar with.

Antti Salminen’s novels and philosophical writings would speak to many readers, as they do speak to Finns. If you’d like books that mix Soviet esotericism, Paul Celan like precision, slapstick humour, apocalyptic philosophy and prayer and include the war between plants and mushrooms, you need to claw your way to his books.

There are so many poets I admire and would love to see more in English. Petra Vallila, Reetta Pekkanen, Pauli Tapio, Henriikka Tavi… these are the first to come to mind, but I could just as well list many others. Tua Forsström, who is Finnish but writes in Swedish, has hopefully been widely translated. Reading her poems always makes me remember why I love reading. Sini Silveri is an interesting, powerful poet, a sort of mix between Kathy Acker and Sean Bonney. But the three first mentioned are the ones I treasure as immense gifts, and to know their work has made my life infinitely richer and more worth living.

The three books I’ve been reading today are Monica Fagerholm’s Eristystila/Kapinoivia naisia, Don Paterson’s The Poem – Lyric, Sign, Metre and Bahtin’s Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. This kaleidoscopic selection changes all the time, but these are the latest I’ve had under my tired eyes.

AV: I have been reading Ovid’s Tristia which Erkka also has a strong poetic relationship to – also Huysmans À rebours, and the unexpurgated journals of Nijinsky, for a forthcoming piece in print only in The Toe Rag. Maybe you’ll see it in Finnish someday!

Or even better: something from both of us on Ovid. Or art or uh, Elvish language problems. (we are not disclosing our teenage sins)

LP: Thank you so much for the list to explore & thank you both for taking the time to chat with me. It is inspiring and heartwarming to see the passion for literature in Finland. I hope, for all of us, we see more books coming out of Finland in translation.

****

The Chapbook is available in Finnish here.

A.V. Marracinni’s “Mutta on toisia geometrioita” is available here.

Suomennos Erkka Filander.

Leave a comment