Review By Louis Davidson.

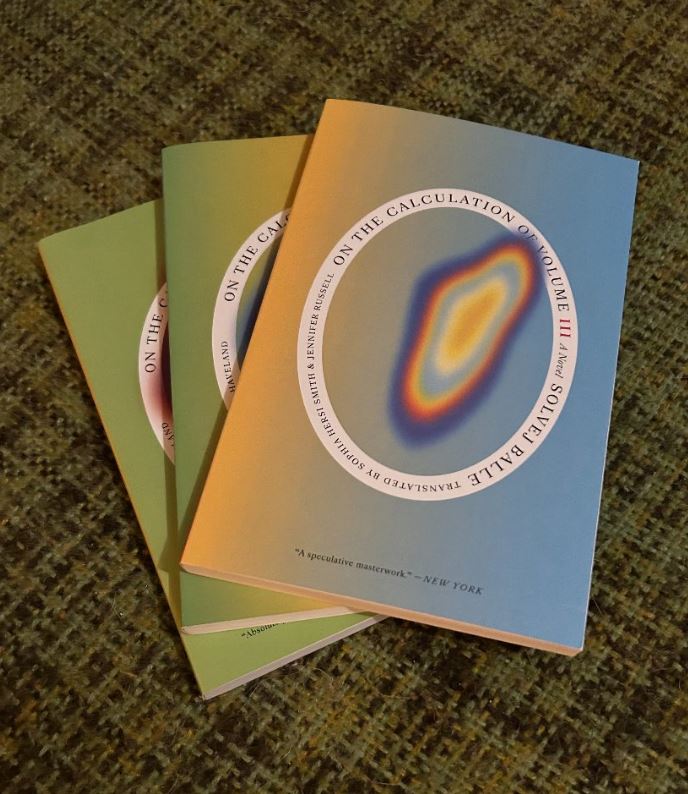

On The Calculation Of Volume III by Soljev Balle,

Translated by Sophia Hersi Smith and Jennifer Russell.

New Directions.

85/100

By the latest book in On the Calculation of Volume, Tara Selter has lived through the eighteenth of November over a thousand times.

She wanders, ghostlike, through this bizarre experience, observing, noting, in turns allowing herself to succumb to it and in others energetically engaging in studying Ancient Rome. She travels throughout Europe, from her home in France to Düsseldorf to Cornwall and back again, and still the days won’t start again. And the clock is unlikely to start ticking again any time soon – three more volumes have been written in Danish, awaiting English translation. Yet another waits to be written – giving us a total of seven.

Unlike in Groundhog Day, Tara doesn’t rebegin every day in the same spot. The distance she covers remains covered as the clock resets. In fact, the whole mechanism by which she has become unstuck in time is the series’ most interesting and unnerving device. There’s no consistency, no neatness, no simple rules to follow. Some objects will follow Tara from one ‘day’ into the next; others won’t. Sometimes the impact of her reliving the same day again and again will be felt in the world around her: shops run out of yoghurt, restaurants run out of dishes: she is, in her words, ‘a monster stuck in a single day, devouring its world one bite at a time’. The fact that the cycle is messy and imprecise gives Tara an uncertain relationship with it. And in my opinion it makes the cycle seem that much crueler – as if it has whims, as if it decides on a case-by-case basis what Tara is allowed to hold onto, what she can keep, and what must be lost.

****

****

The general tone of these books has been sombre. Reading them reminds me of experiences with depression: the monotony, the dispiriting isolation, the overwhelming sense of some fundamental, nameless thing having gone wrong. There are passages in all of these novels which are genuinely moving, and they all revolve around loss, saying goodbye, understanding the temporary nature of things. In this volume she attempts to return to Clairon-sur-Bois to be with her husband, Thomas. But she realises that, after 1543 days in the cycle, she is a different person. She can no longer reach him, she feels like a burden: ‘I made his day melancholy. How could I do that? No. I couldn’t. Not anymore’. After which point she retreats to the spare room, where she hides and listens to the sounds of the house, ‘They are the sounds of what I have lost. I cannot get used to the loss of Thomas, of his body moving around and making sounds’. This section of the novel is the strongest, and it underlines that the cycle is heartless in that it does not offer any replacement structure for what it has taken away. If you’ve ever been depressed – this will be a familiar feeling.

Balle renders this in sharp, precise prose. The contrast between her precision of observation and the slippy, messy feel of the cycle sharpens the sense that something has gone wrong. Indeed, Tara seems uninterested in guessing the mechanism that has caused her to be stuck in November the Eighteenth. She ‘no longer believe[s] in such simple explanations’. Instead of getting tied up in metaphysics or half-believable exposition dumps, Ballej renders the cycle as one of pure experience: sounds, sights, smells. Tara succumbs to the sense-repetition. Sounds, sights, smells, once so small as to not be noticeable, take on huge import. In a sense the novel reads like one dealing with grief – the kind of grief that comes after losing a loved one in a pointless death: you just have to accept the blunt fact of it.

This tone could start to become a bit oppressive. In fact, if I had one issue with our narrator, it would be her reluctance to introduce any humour into the novels. While there are moments in III, they are few and far between. I realise that these novels aren’t aiming to be knee-slappers, but for a series that’s selling point is its exploration of all aspects of a repeated 24-hours, is there really no place for wit? It’s a similar issue that comes up in Fosse’s Septology and Knausgaard’s My Struggle: these epic, multi-volume sagas that try to encapsulate all of life and yet leave out the idea that anyone might be funny about anything at any point.

Not that I want or need a pie-in-the-face-gag, but it would go a long way to leaven this rather bleak series of novels. Thankfully, we are introduced to a new character: Henry Dale, also trapped in the eighteenth of November. While his viewpoint livens things up and adds some diversity to the musings on the cycle, he is unfortunately too close to Tara. He also seems unconcerned with eating or laughing, he also defaults to bemused pessimism. Add to that that he is a university professor (already a much overrepresented career in literary fiction), to match Tara’s career as an antique bookseller, and you end up with another version of the same character. Rather than offering a new viewpoint, we have the same one inflected through slight differences.

Despite these hesitations I would recommend On the Calculation of Volume. Many reviews call the book ‘hypnotic’ (a word that seems like a euphemism for ‘readable’ with a literary inflection) and I would agree with that assessment. Balle performs a kind of sprezzatura with her prose: a studied effortlessness that communicates a lot in a short time. What it communicates has to do with love, loss, hope, and togetherness, all through a disquieting scenario being faced by a resilient narrator.

FFO: Olga Ravn, Harry Martinson, Annie Ernaux, Karl Ove Knausgaard & Dag Solstad.

Buy Here.

Leave a comment