By Isaac Campos.

Melancholy I – II by Jon Fosse.

Trans. Damion Searls & Grethe Kvernes.

95/100.

Dalkey Archive Press.

****

The Danger of Embodying Every Book I Read.

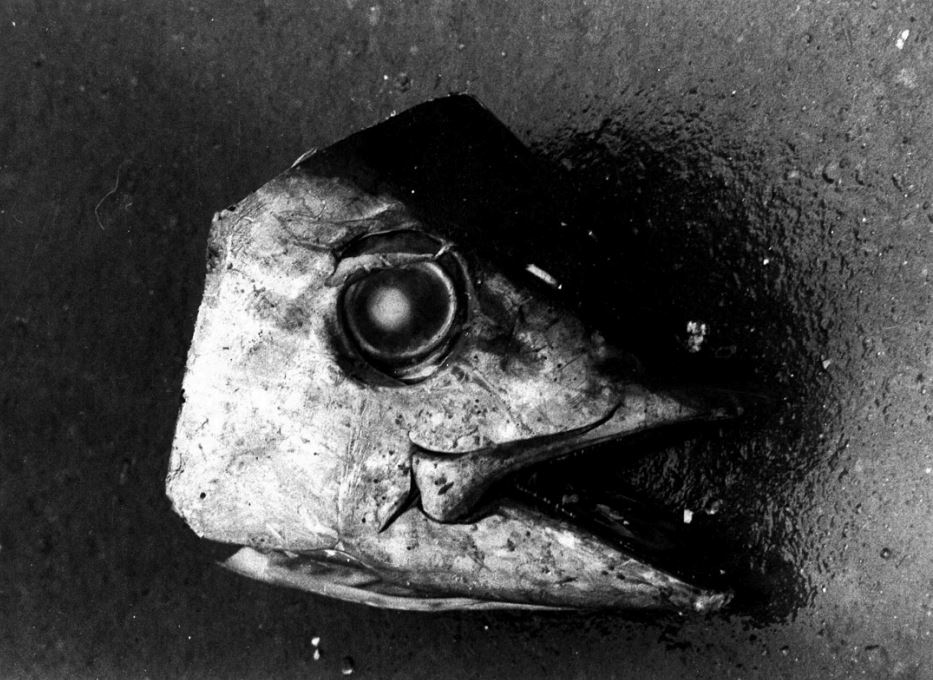

“She looks into the fish eyes, rigid, black, and the fish eyes look straight into her and suddenly she feels like she is these fish eyes, she isn’t what’s being looked into by the fish eyes, she is the fish eyes” – Melancholy II (pg. 409).

****

Daido Moriyama, Untitled (Fish Head), 1978

****

This essay is not a review or observation of Melancholy as a literary study. This is not a literary essay; I am writing of the reception of a feeling. A confessional narrative on the transmutational embodiment one may, on occasion, allow without resistance in reading anything with density. When difficulty meets acceptance only patience can bring light before the darkness already let through.

Fosse came to me at a slow and desperate pace. In Melancholy, I found stretches of prose denser than anything I’ve read so far. Stretches and stretches of madness in repetition – circular lost thinking without end. Ravings and delusions, I had entered the mind of a madman, a man I could not blame nor praise and my sympathy rose and fell with his temperament. I could not weigh my own feelings in this novel. I went through Septology and felt invincible, a nearly seven hundred page tome of magic but still I was beginning to put this book down. In the case of Septology; I picked it up, loved it, shared it with a lover, fell out with said lover, and dropped it before I could reach the second volume. I renounced entirely literature, writing, and God and then the book found me again three years later and I found again at the center of me: literature, writing, and God.

We follow Lars Hertevig, a talented but poor Norwegian painter. Right away are we possessed, by this haunting prose that loops and loops, and we find ourselves asking if it’s us, Fosse, Hertevig, or the very elements at play within the writing that is tricking us — making us unsure. Lars is a special type of artist, a feeling type, someone with exceptional talent, born with the ability to see the glimmer; alien rhythms, the ghostly and metaphysical – in rare moments of clairvoyance & metaphysical abstraction. Lars can catch glimpses, glimmers, shining pieces of life and paint them away. In the novel he is sent off to Germany to study landscape painting and possibly make a name for himself in that right.

It is important to note coming into this work my expectations were misaligned with the identity of the novel entirely. Coming from Septology I imagined similar thematic elements in terms of the process of painting, art-making, etc; I was expecting wise insights from a wise painter who found himself. The novel has hardly any of that. Instead of witnessing Lars behave as Asle (Septology’s protagonist) and dive into the lines of a painting, the shining of a painting, the brushstrokes, the taking apart and making and stretching of a canvas – instead of all this my privileged perspective crumbled at the onslaught of the true reality of the suffering artist. The stream-of-consciousness of Lars is what we would see if Septology were attuned to the sights of Asle’s alcoholic doppelgänger. I was immersed into and inspired by what Septology gave me, the beauty of that life hardly had attuned into the suffering — that novel out of the struggle, turns the mirrors away, the monotony born from the chaos is our light and hardly do we meet the noise.

The external forces that make us imperfect, the ardor, the vitality that drives life surging within us—when uncontrolled, unrestrained what are we left with that is human? What are we left with at all, there in that human? Hardly do I feel the same feelings to romanticize the story of a body and mind strained, so confused, and so tortured. Leaving through the strokes are relatable pieces of humanity — how Asle connected to the world broken; alone. For Lars he communicates his gift, his vision to the metaphysical the only redeeming light to his humanity despite his lack of understanding, despite his inabilities he is skinning himself in these pieces showing that he is alive. If not painting, Hertevig still creates, managing solely with coal and driftwood making pictures of his sister, the clouds, anything.

The novel floats deeply through its prose, visions, flashbacks, and illusions. Warping back and forth, yet we hardly question the meaning of each moment – every glimpse a potential painting, inspiration; photomontages become the language of the present; we soon grow accustomed to Lars’s sense of time and motion:

“and now what I want most of all is to see you stand up and then you will stand there with your back swaying gently, in your white dress, with your softly rounded chest, you will stand there and then you will let down your hair. And your hair will stream down over your shoulders. You will stand there and look off to the side, down at the floor, and then I’ll stand up, I’ll walk over to you and then I’ll put my arms around you, press you to me, then I’ll stand there and hold you tight, press you to me, all I want is to stand there and press you to me and breathe through your hair. All I want is to stand there. Stand there and press you to me. And then you’ll put your arms around me and then we’ll stand there. We’ll just stand there. Stand there quietly, stand right next to each other, stand there right up next to each other.” – Melancholy I (pg. 21)

****

Masahisa Fukase, Kudan Church 1964 from the series Yoko © Masahisa Fukase Archives

****

We witness so much within the play of memory, forgetfulness and love that lingers within many of Fosse’s novels but here exists the enigmatic embodiment of that motion—inexpressible, consistent chaos. Reality, redundant, is ripped to shreds and put back together with paint and plaster, a mess, but the reality of that beauty is still there magnificent on its own with its own little halo, all tattered. Next to suffering, isolation, and at the crumbling of familiar relationships our spirituality rises in the humidity, condensating our sense of reality—understanding; people, family, friends. Every one of these themes intertextually aligns with what’s seen in Aliss at the Fire and Morning and Evening (excluding Septology). Everything becomes fragmented and Lar’s artistic keenness is left to bare, his only tool for his survival, to base his reality; to shape meaning.

The novel funneling into the stream of Lars’s mind gives the same experiential feeling as drowning, with no sense of how to swim, – only gasping for breath in which we hardly rise out of the depths to do so when again we feel this otherworldly pulling of weight at our heels. Sticking with a novel longer than one should is something I would never recommend to anyone. You rest with the weighing feeling of whatever was unfinished. In this case everything was madness for me everything gestation and birthing (Rilke).

I drowned again and again, with Lars, and came up again and again, with Lars. And the voice that is there; that speaks to every and any artist, these people understand well the negligence and rejection Fosse emphasizes in this novel(something that he had to work through early on in his career). The artistic intuitive voice has hardly meaning or form, it is a sense of molding, it glows and carries a buoyancy of water. The artist type feels and understands the looseness of that voice, its proximity to madness. Form, community, and recognition necessarily mean nothing in confrontation with art in its purest form. We see this through the respect Lars’s talent garners within the community of painters that despise his attitude and mock his character and peculiarity. True art is found in the people truly capable enough to see, hear, and most importantly feel things in their purest form. Art is an act of listening.

“Because the snake is slithering, he says. Yes, you’re right about that, Alida says. I know the serpent’s slithering, I’ve seen it myself, Lars says and he stands there, with those short legs of his, with his long back, and I see Lars staring down at the ground. Yes, you do know, Lars, I say. And they don’t know a thing about art, Lars says.” – Melancholy II (pg. 229).

“And for me, the act of writing is one of listening – when I write I never think it out in advance, I don’t plan anything, I proceed by listening.” – Jon Fosse (in his Nobel Lecture).

Concluding on Lars, and more importantly embodying those visions and his mind. I have to say in absorbing the talented and gifted you also drench yourself wholly in the world of someone fighting, beating soundlessly against a wall unheard. Living as an unnatural, unwilling, abnormal, unheard, unable to be understood nor understand. Going painstakingly through the novel my world began to be muted, hardly making my way through this prose—his mind—did I also feel that I had a place to stand, a place to ground myself.

Floating in ether, behind this wall of memories; behind the waterfall… do you see me? The light glimmers, reaching my eyes as my hand reaches through — but the mist drowns me out.

And the beauty of the shining stones in this grotto behind the water, they are with me, and I see and understand. Me and Lars see it and understand, they are with us.

The rocks and their shining iridescent refractions; sparkling — of the light in noonday making rainbows out of water mist.

Everyone, anyone can see beauty and understand it there, in something, or other, but where in what place, in what saying, do we hear the danger of holding it?

****

Island Borgøya (1867) – Lars Hertervig

****

References:

Jon Fosse “A Silent Language” (Et stille språk), on December 7, 2023. Translated by Damion Searls.

Amy Ireland, Alien Rhythms, Amy Ireland. 2019 https://zinzrinz.blogspot.com/2019/04/alien-rhythms.html (Ireland).

Rilke, Rainer Maria. “Letters to a Young Poet” (Briefe an einen jungen Dichter) Translated by Stephen Mitchell, Vintage International, 1989.

Leave a comment