Review by Noah Vølund Fechter.

they by Helle Helle.

Trans. by Martin Aitken.

New Directions.

88/100

Sometimes I wake up to texts from my mom about Helle Helle. One morning she sent me a Danish government page about literature,where Helle is presented as emblematic of ‘minimalism.’ In Denmark that’s a 1990s literary movement identified chiefly with female fictionists. I think it’s more interesting when Helle’s associated with Hemingway’s ‘iceberg technique,’ but whatever, it’s just important we have something to talk about.

Helle Helle is a massive author in Denmark. She’s won prizes, been assigned to schoolchildren, and the cashier at Arnold Busck will tap the cover and say “hvaaa, dette er rigtigt godt” before you spend 250 DKK on something she wrote.

I like Helle Helle more than my mom does, she’s only read Ned til hundene. Until recently, I had only read This Should Be Written In Present Tense, the only Helle book translated to English for almost a decade. Soon I’ll stop telling people that I’m shocked how little of her we have to read, because New Directions will publish they in February 2026, and three more works are slated to follow. It is strange and inspiring to have this one.

****

****

they is the first English translation of a Helle Helle work set in Lolland, the region of Denmark where she’s from. Railway-ferries from Germany landed in the southwestern port Rødby until 2018 (another of Helle’s fictions takes its name from the line, Rødby-Puttgarden). Today a tremendous underwater tunnel is under construction replacing that ferryline, which will perhaps reconfigure the logistics of Scandinavia entirely. I’ve been on a Facebook page where old folks from Rødby post pictures of huge sandlots and siteworks as the tunnel work progresses. Helle’s fictions are beautiful cultural memories of Lolland around the time she grew up, frozen into static motion. In another 40 years, we could expect the region will be reshaped by industry.

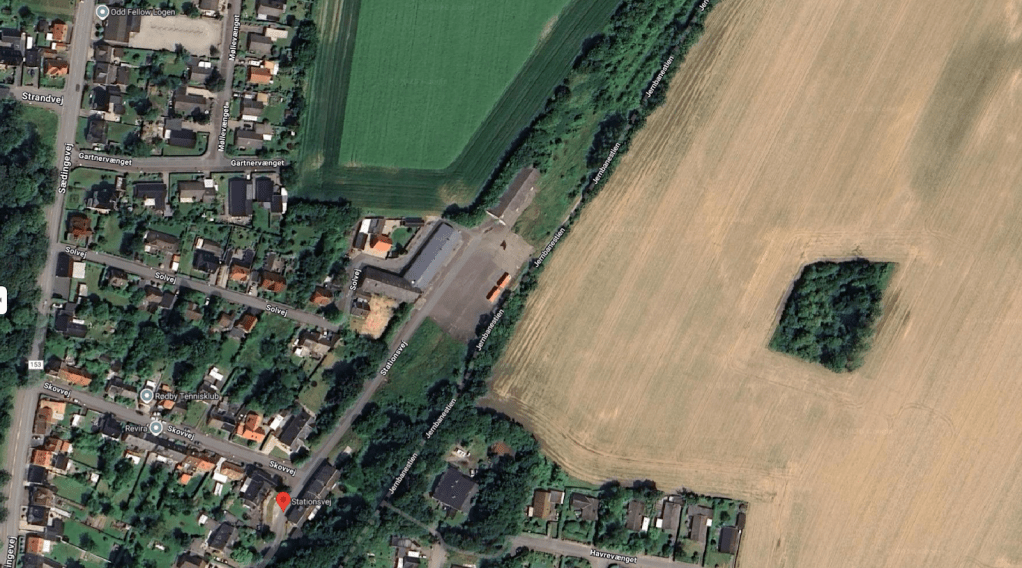

Throughout they, Helle uses Lolland’s endonyms with a familiarity that belies how many of these are also laser-specific. The daughter and her mother live at one point on ‘Kongeleddet.’ For that term, Google Maps goes right to a four-pronged array of modernist apartment blocks in Rødby. Later, the daughter goes to a boy’s house party in Gerringe, which appears to be just two farms and just one home, huddled along a bend in a byway. There is only one home on earth where the boy could’ve lived. My favorite sentence in the book goes “At the bottom of Stationsvej it turns out there’s a station.” There actually was.

****

****

they is a short book about grief, or about life, or how life happens as we die. More directly it’s about the daughter (most often she’s called by her pronouns, but she’s also “the daughter”) and her mother (most often “her mother,” but she also has pronouns). They’re them. Everyone else has a first name, or has two first names, which is a Danish thing. The daughter starts high school and makes fast friends with Tove Dunk, who’s popular, but nice. The daughter’s popular too, really, even with boys. But she doesn’t have a particularly strong connection to any of them; I remembered the names of the three or so boys she undresses around, but the features melt away. This is both a feature of the narration and the plot.

The book’s content and expression are isomorphic, really, like Adorno said he liked about Schoenberg. It has a unique affect, at once sentimental yet banalized. The narration has no omniscience and doesn’t present thoughts. The actions and details chosen are reflective of the daughter’s consciousness, but in a way that runs parallel to her.

The work feels alien and specific, close and disjoint, drab and colorful. Everywhere. A collection of events without rationalization, which don’t matter. Nobody’s morally good and everyone’s worthwhile. It’s strange and ceaselessly compelling, almost musical. Liquid, painted, felt.

****

In a sleight, the book begins with past tense statements about her mother. The rest of the book has a plot in present tense: her mother has a disease, she phones a nurse, hears the prognosis. Eventually her mother has to stay at the hospital, and she has to live alone. Her mother hands her all the cash in her purse. She decides to spend none. She empties the pantry, cooks (presented in uniquely granular detail). Her undone laundry starts to cover everything. Sometimes she lies down in it. Eventually her mother leaves the hospital (it’s unclear if the prognosis has changed at all). She and Palle watch her mother, wonder what will become of things. Sometimes she wakes up in the night, finds her mother writhing in pain.

There is an interpretation in which the daughter’s grief explains the book’s expressionist form altogether. In grief, we halo little things, collect them. Details steal into our attention, reach us in our shame, become memories. One day we find them again and they’re just themselves. The daughter is never suffused by a numbness to life, but by this strange, staccato receptivity.

They move often. Many of the book’s chapters are page-length entries which read like prose poetry, often focused on a single place where they live. My mind fixated on one of these paragraphs: they live in a home where an adjacent road aligns with their living room window, such that every pair of passing headlights fills the household. When the paragraph ends they’ve moved again. They keep moving, over and over. Eventually they live out in the farmland. One night, her mother asks for cauliflower gratin. (Bob offers to give her one, an offer which she doesn’t accept.) She wakes up early. I imagine she plans to steal a cauliflower from a field. The book ends.

****

In a 2015 talk, Helle Helle explained that schoolchildren in Denmark are made to read her stories, so that they can be taught ‘not to read her in the wrong way, there are no symbols.’ Whether she affirms this idea, herself, is left for interpretation. Thirty minutes earlier in the talk, the host suggested that a train station is symbolic of a coming-of-age threshold. The author adjudicated: “It’s not.”

Part of me feels that they might confound the English audience, for whom its cultural touchpoints are alien. It’s harder for us to know if the bread is just bread. But I think that they also presents its own context with a real, bare, material force. The Danes are Danes, the knækbrød is crispbread, and they were them. These things are suffused with a stonelike humor and melancholy, worthy of attention, worthy of memory. They just were.

****

****

Footnotes:

they is the translation of Helle Helle’s De [2018].

This Should Be Written in the Present Tense, the translation of Helle Helle’s Dette burde skrives i nutid, was published by Vintage in 2016, with English translation by Martin Aitkin. The original was published in 2014 by Gyldendal. There’s a 2015 talk, at Edinburgh International Book Festival, where Helle described that her Danish comma syntax does not translate into English writing, and as a result her characteristic, ‘musical’ rhythm in Danish is distorted or removed in her English translations. (Go to 50:56 in this video. Specifically, she just says that ‘Martin told me,’ but she doesn’t seem to disagree.) Aitkin will, quite soon, be the translator of at least five Helle Helle books (read the next footnote).

The translation of they will be followed by three subsequent novels: BOB [2021, ostensibly named for the character Bob who also appears in they], Hafni fortæller [2023, literally ‘Hafni tells‘, certainly named for the character Hafni who also appears in they], and finally Hey Hafni [2025]. New Directions secured the English rights to the two Hafni books; UK-based Akoya Publishing has the English rights to BOB (they’ll launch in 2026 with ten books, BOB is one of them). Martin Aitkin has translated or will translate all of these.

Rødby-Puttgarden was published in 2005 by Samlerens Forlag. Nobody has the English rights, but it’s the work of hers that won the Danish Kritikerprisen, which doesn’t imply it’s her best work (nobody’s ever won the award twice), but explains why it’s one of her best-known books.

Whereas I’ve written “In a 2015 talk, Helle Helle explained…,” I am referring to around 41:12 in this video, in which she says “I have been traveling around to Danish schools for many years, talking about my short stories that [teachers] use in [their] Danish lessons, trying to explain how [students] shouldn’t read them, and understand them,– that there are no symbols … I [make additional income] that way, but it’s not easy.”

Whereas I’ve written “The author adjudicated..,” I am referring to around 14:19 in the same video as the preceding footnote, in which she says “Oh, so you find the station symbolic. It’s not.”

****

FFO: Marcel Proust, Solvej Balle, Olga Ravn.

Buy Here.

Leave a comment