Review by Ursula Carroll

The Calf by Leif Høghaug, translated by David M. Smith

Out Nov.11 on Fum D’Estampa, via Deep Vellum

94/100

I’s a-settin here a-thankin an’ a-writin an’ soon enuff you like’ta realize that everythang I’s a-thankin an’ a-writin… is the way that language moves on the page and in the air are two very different things. I have never seen that laid out so plainly as it is in The Calf by Leif Høghaug, translated by David M. Smith. The Calf is many things. It is a novel about memory, a novel about violence, it is a novel about trauma, but above all it is a novel about the outer limits of language. It is a novel about how far the written word can be pushed, it is a novel about the place where speech and text no longer converge, and it is one of the most satisfying books I have ever read.

In rural Norway; a couple hours north of Oslo; a “meckanickal” gnome; a pseudo-marionette tries to remember a summer night. He works his menial job in the “unnerworld” and thinks and tries to remember. He, along with his cadre of friends, either took part in or witnessed or experienced something that our gnome is very disturbed by. The cast of characters is bizarre, unsettling at times. A moon-woman who dictates work, a giant, an alien, it is never immediately clear what shape any one figure is taking. Almost nothing is immediately clear in this book. Our gnome is grasping, getting closer and closer to remembering. As the book progresses, the circle tightens, the narration becomes slightly more reliable. The plot coils in on itself, becoming tighter and tighter and tighter until we get to a possible reality, a possible telling of that summer night our gnome has tried so hard to “fergit”.

The barn-gnome struggles so much to remember, he’s pushed so much of what happened that night out of his mind. From his office that makes some sort of comfort object that white collar workers can ingest or insert to relieve stress, there he sits, trying to work it out. At its core, The Calf is a story about violence and trauma. Deep within the gnome’s noggin, somewhere in the crannynooks of his mind, he has tucked away the images of some horrific night. It is a familiar traumatic response, it is relatable. It is not entirely clear what is more responsible for our gnome’s desire to “fergit”: what he saw or what he experienced. Our gnome exhausts himself posturing, explaining the tough guy boyish exploits of his friends. The terrible night is the result of comical exercises in masculinity, and for what? What does he have to show for it?

The Calf ebbs and flows in and out of genre, impossible to pin down. It is mystery, it is science fiction, it is Lutefisk Western, it is tragicomedy. It is an experiment. The Calf is written entirely; from start to finish; in southern American dialect. There is an included glossary that is entirely necessary, not only is the language in this book using established vernacular, but created language. David M. Smith, in translating this, was faced with the task of converting Norwegian terms with no English equivalent to southern dialect. The anachronism of the southern American dialect being used to describe Norway is almost funny. A language I associate with being humid and hot coming out of the mouths of characters in a cold, wet landscape is an image that was always in the back of my mind as I read.

This was not just a rogue choice by the translator; the original Norwegian is also written entirely in the local rural dialect of the setting. In the translator’s note, Smith states that the original dialect was chosen because it was the language of Høghaug’s father, and Southern vernacular the language of Smith’s so it was the natural choice. Norwegian is a gentle, musical language and Southern American English is a gentle, musical dialect, the pairing makes perfect sense to me. As I understand, the original text looks strange to native speakers, they find it to be challenging, as English speakers will with the translation. That is not to say it is not an incredible read, it is worth the effort. There were times where I thought it necessary to read the book aloud to understand it. The sentences are beautiful, the rhythm and weight of the word choice so deliberate and well thought out, I found myself being equally interested in the characters and story as I was with the actual words on the page. The story wrapped in on itself and I spent more time considering how written word and spoken word diverge.

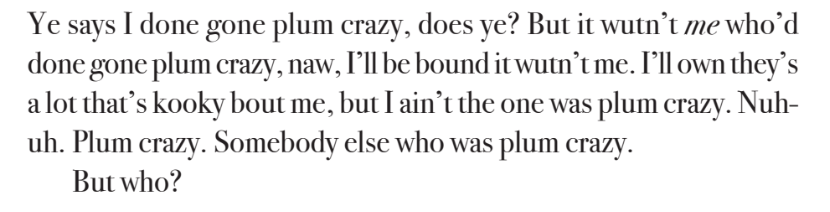

I was thinking about how far apart they can be. In American literature, there is a strong tradition for Southern vernacular use. I have read Twain, Faulker, Hurston, etc, but this is really the only vernacular with a strong literary tradition. Is this because it is the language that is most easily captured in text? I have a New England accent, I have never read literature in my speaking voice. Would it even be possible to have written this book in my voice? When I read this sentence in The Calf “They’s a gallopin an’ gallopin on by an’ the warsh-tub noggin is tryin to fergit,” I can hear it clear as day. I know that voice quite well. I have had neighbors with that voice. In this book, the written word and the spoken word are one and the same, from beginning to end. I think there is a kind of simplicity in this, the marriage of the spoken and the written. It strips away formality, tension, and forces a sort of familiarity. I do not know if all books need to be written as spoken, but I do think it is worth trying.

Reading The Calf; a book written in a voice I can hear; made the spiraling plot, the mysterious characters, critters, biblical allegories, violence, haze, all of it; feel like a story being told to me. I didn’t feel like I was reading a novel, I was listening. Everything about this book swirled around in my head for days after I finished reading it. Phrases and scenes coming together in my warsh-tub noggin to help with “connechun, contextualizashun,” and weaving The Calf into my mind forever. The experiment is a success.

FFO: Shadow Ticket and needing something new to make their head spin; taking notes; James Joyce.

Buy Here

Leave a reply to Lønningspils Year End 2025 – lønningspils Cancel reply